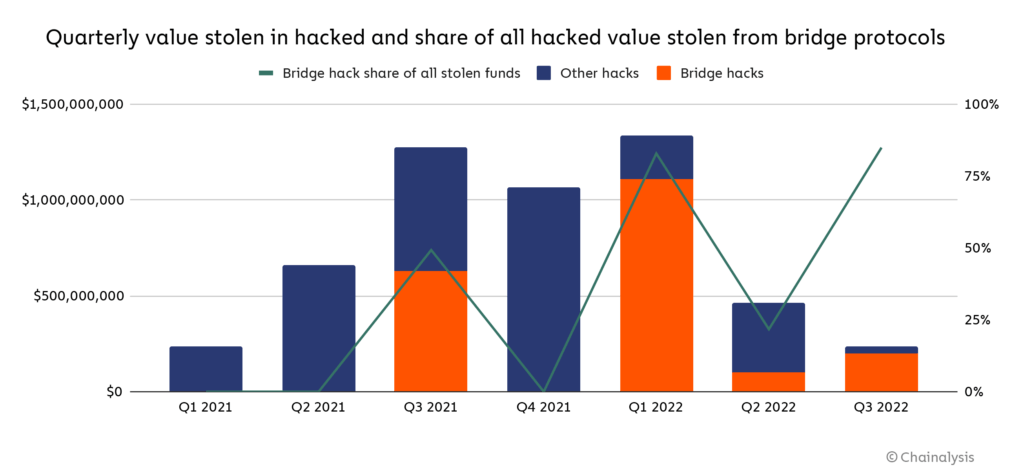

Following exploit of the Nomad Bridge, Chainalysis estimates that $2 billion in cryptocurrency has been stolen across 13 separate cross-chain bridge hacks, the majority of which was stolen this year. Attacks on bridges account for 69% of total funds stolen in 2022 so far.

This represents a significant threat to building trust in blockchain technology. As more value flows through cross-chain bridges, they become more attractive victims for hackers. Even more troubling is that bridges are now a top target for North Korean-linked hackers, who – according to our estimates – have stolen approximately $1 billion worth of cryptocurrency so far this year, entirely from bridges and other DeFi protocols. For perspective, South Korea’s government-run statistical agency estimates the country earned $89 million from official exports in 2020.

The good news is that these services can take steps to protect themselves. And in the event of a hack, they can leverage the transparency of blockchain technology to investigate the flow of funds and ideally prevent attackers from cashing out their ill-gotten gains.

Cross-chain bridges are designed to solve the challenge of interoperability between different blockchains. A cross-chain bridge is a protocol that lets a user port digital assets from one blockchain to another. For example, Wormhole is a cross-chain bridging protocol that allows users to move cryptocurrencies and NFTs between the various smart contract blockchains such as Solana and Ethereum.

While bridge designs vary, users typically interact with cross-chain bridges by sending funds in one asset to the bridge protocol, where those funds are then locked into the contract. The user is then issued equivalent funds of a parallel asset on the chain the protocol bridges to. In the case of Wormhole, users typically send Ether (ETH) to the protocol, where it is held as collateral, and are issued Wormhole-wrapped ETH on Solana, backed by that collateral locked in the Wormhole contract on Ethereum.

Bridges are an attractive target because they often feature a central storage point of funds that back the “bridged” assets on the receiving blockchain. Regardless of how those funds are stored – locked up in a smart contract or with a centralized custodian – that storage point becomes a target. Additionally, effective bridge design is still an unresolved technical challenge, with many new models being developed and tested. These varying designs present novel attack vectors that may be exploited by bad actors as best practices are refined over time.

Just a few years ago, centralized exchanges were by far the most frequent targets of hacks in the industry. Today, successful hacks of centralized exchanges are rare. That’s because these organizations prioritized their security, and because hackers are always looking for the newest and most vulnerable services to attack.

While not foolproof, a valuable first step towards addressing issues like this could be for extremely rigorous code audits to become the gold standard of DeFi, both for those building protocols and for the investors evaluating them. Over time, the strongest, safest smart contracts can serve as templates for developers to build from.

Cryptocurrency services – including but not limited to bridges – should invest in security measures and training. For example, with North Korean-linked hackers in particular, sophisticated social engineering tactics that take advantage of the trusting and carelessness of human nature to gain access to corporate networks has long been a favored attack vector. Teams should be trained on these risks and warning signs.

Source: https://blog.chainalysis.com/reports/cross-chain-bridge-hacks-2022/